Friday, April 08, 2005

Watch Jay Learn

William Zinnser's book On Writing Well is a well-written book on writing well, so well written that I remember the great time I had devouring it some twenty years ago. In a chapter about editing and polishing one's words, Zinnser shows a page of his own work, marked-up with self-imposed rearrangements, deletions, and word changes. Instead of reading about Zinner's writing, I was looking at the real deal.

Looking over Zinnser's shoulder at that single page changed the way I write. If he can go over such picky little nits, so can I. If he can edit an essay half a dozen times, so can I. If this is part of the drill for writing, I'll do it myself. And now I do.

We don't get the opportunity to look over many people's shoulders as they work, somehow preferring to deal with a description of the thing rather than the thing itself. So I'm going to look over a few shoulders for you, starting with my own.

A book on learning, something that takes place in our heads, needs a model of how the brain works. I decided to think about that while walking in a park above the City of Oakland.

A book on learning, something that takes place in our heads, needs a model of how the brain works. I decided to think about that while walking in a park above the City of Oakland.

The park is the on the grounds of what was once the estate of Joaquin Miller, a colorful local essayist and poet whose wild west sagas once charmed the British Royal Family.

Walking is my exercise; it's hilly enough here that a steady pace and swinging arms are enough to get the heart muscle in the zone. After forty-five minutes, I sat at a picnic table with my notebook to reflect on my thoughts.

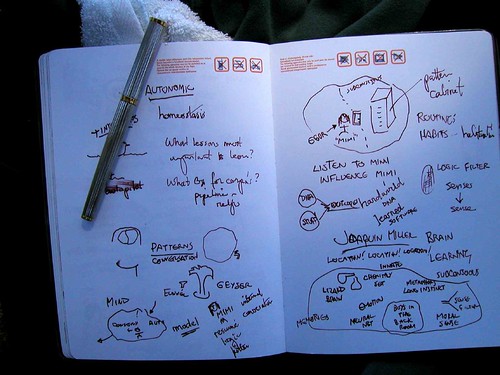

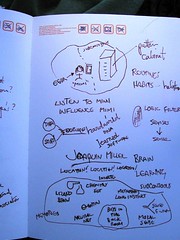

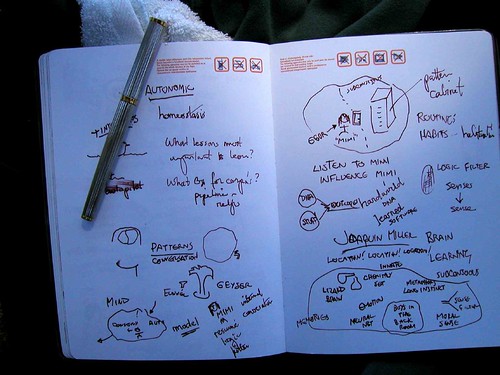

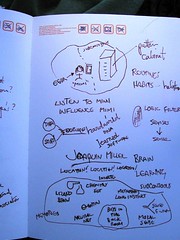

This is typical for me: fragments of ideas, chains of thoughts, doodles, maps, connections, and scribbles. My writing tool of choice is a Waterman fountain pen, although it makes me sloppy. The 5" x 7" notebook is unlined. Drawing helps me think. The only time I'm without a notebook at hand is when I'm taking a shower.

My next step is to reflect and then convert the ideas into words and images on the computer.

In this case, the first draft result is here.

Looking over Zinnser's shoulder at that single page changed the way I write. If he can go over such picky little nits, so can I. If he can edit an essay half a dozen times, so can I. If this is part of the drill for writing, I'll do it myself. And now I do.

We don't get the opportunity to look over many people's shoulders as they work, somehow preferring to deal with a description of the thing rather than the thing itself. So I'm going to look over a few shoulders for you, starting with my own.

A book on learning, something that takes place in our heads, needs a model of how the brain works. I decided to think about that while walking in a park above the City of Oakland.

A book on learning, something that takes place in our heads, needs a model of how the brain works. I decided to think about that while walking in a park above the City of Oakland.The park is the on the grounds of what was once the estate of Joaquin Miller, a colorful local essayist and poet whose wild west sagas once charmed the British Royal Family.

Walking is my exercise; it's hilly enough here that a steady pace and swinging arms are enough to get the heart muscle in the zone. After forty-five minutes, I sat at a picnic table with my notebook to reflect on my thoughts.

This is typical for me: fragments of ideas, chains of thoughts, doodles, maps, connections, and scribbles. My writing tool of choice is a Waterman fountain pen, although it makes me sloppy. The 5" x 7" notebook is unlined. Drawing helps me think. The only time I'm without a notebook at hand is when I'm taking a shower.

My next step is to reflect and then convert the ideas into words and images on the computer.

In this case, the first draft result is here.