Thursday, September 29, 2005

The ever-expanding project

You've heard of scope creep? That's when a project takes on a life of its own, pushing its boundaries ever wider. I'm facing scope explosion. Every evening while I sleep, the tendrils of my subject reach out to form new connections. How can I leave out __________ (fill in the blank)? My mindmaps are mushrooming exponentially.

My tale of informal learning would be incomplete without deep dives into complexity theory, cognition, collective intelligence, co-evolution, collaboration, conscious evolution, etc., and that's just the beginning of the list of words that begin with "C."

I am Mickey Mouse in The Sorceror's Apprentice. The water is rising faster than the brooms can carry it out. Stacks of books and articles and scribbles tower over my desk. So much to read, to learn, to integrate into my thinking. So many wonderful people to talk with about this. I'm about to drown in thought. And I have about ten working days left before heading to Learning 2005 and then Taiwan and then Abu Dhabi and then Berlin. My manuscript is due soon thereafter.

I must hop out of this escalating cycle

else risk burning out

so I'm changing course

The unified field model of informal learning

is a grail I will not reach

on the present journey

Instead I will be content to light the fire

to tantalize with examples

to make readers crave more

After all, research has found that lessons

left incomplete stick twice

as well as those left open

William Carlos Williams:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

Friday, September 23, 2005

Rules for being human

You may like it or hate it,

but it's yours to keep

for the entire period.

You will learn lessons.

You are enrolled in a full-time,

informal school called life.

There are no mistakes, only lessons.

Growth is a process of trial, error

and experimentation.

The "failed" experiments are as much

a part of the process as the experiments

that ultimately "work".

Lessons are repeated until they are learned.

A lesson will be presented to you in various forms

until you have learned it.

When you have learned it,

you can go on to the next lesson.

Learning lessons does not end.

There is no part of life that doesn't

contain it's lessons.

If you're alive,

there are still lessons to be learned.

"There" is no better than "here".

When your "there" has become "here",

you will simply obtain another "there"

that will again look better than "here".

Other people are merely mirrors of you.

You can not love or hate something

about another person unless it reflects to you

something you love or hate about yourself.

What you make of your life is up to you.

You have all the tools and resources you need.

What you do with them is up to you.

The choice is yours.

Programming is Gardening, not Engineering

Andy Hunt: There is a persistent notion in a lot of literature that software development should be like engineering. First, an architect draws up some great plans. Then you get a flood of warm bodies to come in and fill the chairs, bang out all the code, and you're done. A lot of people still feel that way. I saw an interview in the last six months of a big outsourcing house in India where this was how they felt. They paint a picture of constructing software like buildings. The high talent architects do the design. The coders do the constructing. The tenants move in, and everyone lives happily ever after. We don't think that's very realistic. It doesn't work that way with software.

We paint a different picture. Instead of that very neat and orderly procession, which doesn't happen even in the real world with buildings, software is much more like gardening. You do plan. You plan you're going to make a plot this big. You're going to prepare the soil. You bring in a landscape person who says to put the big plants in the back and short ones in the front. You've got a great plan, a whole design.

But when you plant the bulbs and the seeds, what happens? The garden doesn't quite come up the way you drew the picture. This plant gets a lot bigger than you thought it would. You've got to prune it. You've got to split it. You've got to move it around the garden. This big plant in the back died. You've got to dig it up and throw it into the compost pile. These colors ended up not looking like they did on the package. They don't look good next to each other. You've got to transplant this one over to the other side of the garden.

Dave Thomas: Also with a garden, there's a constant assumption of maintenance. Everybody says, I want a low maintenance garden, but the reality is a garden is something that you're always interacting with to improve or even just keep the same. Although I know there's building maintenance, you typically don't change the shape of a building. It just sits there. We want people to view software as being far more organic, far more malleable, and something that you have to be prepared to interact with to improve all the time.

Bill Venners: What is the alternative to stratification of job roles?

Dave Thomas: I don't think you can get rid of the layers. I think politically that would be a mistake. The reality is that many people feel comfortable doing things at a certain level. What you can do, however, is stop making the levels an absolute. A designer throws a design over the partition to a set of coders, who scramble for them like they are pieces of bread and they are starving, and they start coding them up. The problem is this entrenched idea that designers and coders are two separate camps. Designers and coders are really just ends of the spectrum, and everybody has elements of both. Similarly with quality assurance (QA). Nobody is just a tester.

What we should be doing is creating an environment in which people get to use all their skills. Maybe as time goes on, people move through the skill set. So today, you're 80% coder 20% designer. On the next project, you're 70% coder and 30% designer. You're moving up a little bit each time, rather than suddenly discovering a letter on your desk that says, "Today you are a designer."

Andy Hunt: If the designer also has to implement what he designs, he is, as they say, getting to eat his own dog food. The next time he does a design, he's going to have had that feedback experience. He'll be in a much better position to say, "That didn't quite work the way I thought last time. I'm going to do this better. I'm going to do this differently." Feedback paths contribute to continual learning and continual improvement.

Bill Venners: Continual learning is part of the notion of software craftsmanship?

Andy Hunt: Exactly. First you've got the designer doing some coding, so she'll do a better design next time. Also, you really need to plan how you are going to take some of your better coders and make them designers. As Dave says, will you give them "the letter" one day? Sprinkle some magic fairy dust and poof, they're now a designer? That doesn't sound like a good idea. Instead you should break them in gradually. Maybe they work with that designer, do a little bit of this design today, a little bit of that design tomorrow. Some day they can take on a greater role.

Tuesday, September 20, 2005

Process thinking

Alan Key: It is amazing to me that most of Doug Engelbart's big ideas about "augmenting the collective intelligence of groups working together" have still not taken hold in commercial systems. What looked like a real revolution twice for end-users, first with spreadsheets and then with Hypercard, didn't evolve into what will be commonplace 25 years from now, even though it could have. Most things done by most people today are still "automating paper, records and film" rather than "simulating the future".Visit to Bootstrap

In 2003, the five members of the Meta-Learning Lab huddled around a conference table at The Bootstrap Institute to listen to Doug Engelbart recount the story of his life's work. Doug told us that for fifty years, he had pursued one goal: augmenting the human intellect--to boost mankind’s collective capability for coping with complex, urgent problems.

No success

I asked Doug who best exemplified the spirit of his work. Who had put his ideas into action? "No one," he replied. It was tragic. Fifty years and yet to reach the finish line. Augmentation of intelligence was the very reason Doug invented the mouse, windows, bit-mapped graphics, word processing, and the network. How could such a brilliant mind have failed to enlist some takers?

How to bootstrap

Doug's objective is simple and compelling: "A-B-C's of bootstrapping. Any organization's stock in trade is called here an A-activity; its ordinary R&D work to improve on A is called a B-activity. The bootstrapping strategy serves to improve on B and is called a C-activity. The value of C may be perceived as garnering compound interest on an organization's intellectual capital."

Variants

The work of Chris Argyris is quite similar. "Double-loop learning" involves reflecting on one's learning, asking if there's a better way to accomplish it. Intellectually appealing, Argyris's work has not been adopted widely. When the Meta-Learning Lab talks of "going up to the balcony," it's another case of improving the process and not just the instance at hand. In spite of showing enormous potential returns on investment, not one corporation has shown an interest in funding a project.

What's going on here?

Waiting for someone to arrive at the North Berkeley BART station this afternoon, I pondered why organizations had failed to pick up on something with such enormous and obvious potential. Boiled down to essence, the process of augmenting human intelligence is no more than applying continuous improvement to learning. As Doug wrote long ago, his mission includes:

- Enable a whole new way of thinking about the way we work, learn, and live together.

- Promote development of a collective IQ among, within, and by networked improvement communities.

- Share the A-B-C's of bootstrapping* and support co-evolution of human organizations and their tools.

An Italian tailor has a private audience with the new pope. Upon returning to his neighborhood, his friends ask what this new German pope is like. "He's a 42 Regular," says the tailor. Every profession has its blinders.

Physicians and surgeons

When I was in my twenties, I had an annoying medical condition. I visited my physician weekly. He was a bright guy, a graduate of Johns Hopkins, very articulate. But he couldn't figure out what was going on. He checked my blood. He checked, ahem, other fluids. He sent tissue samples to the lab. No luck. I seemed to have some condition unknown to medical science. After almost a year, by which time my condition had deteriorated significantly, my doctor said, "Ah ha. Maybe this is not a medical problem at all. It might be a surgical condition." I went to a surgeon. He immediately recognized what was going on and scheduled me for surgery at St. Mary's Hospital ten days later.

Going to a specialist I mistook for a generalist, I almost literally lost my ass. I can't resist inserting a bit of humor here. Question: "What do you call the person who graduated last in his class at medical school?" Answer: "Doctor."

You see what you're looking for

Remember the movie Bullitt? Steve McQueen chases the bad guys through the hills of San Francisco in his souped up Mustang. Their cars race down Fillmore Street toward the Marina, jumping into mid-air as they crest each street crossing. I have seen the chase a dozen times since the movie was released in 1968. It still takes my breath away. Not long ago, my wife Uta told me, "Watch the Volkswagen." Now I have a different perspective on the chase scene. Block after block, Steve McQueen passes the same pokey Volkswagen beetle. The movie makers knew that the eyes of the audience would be so glued to Steve's car that they would not even see the surroundings.

The Cobbler's Children

Giving other people advice that's meant for us is commonplace. That explains why most psychiatrists are nuts and why most great learning designers have learning disorders. (See "The Cobbler's Children in the chapter Learners & Their Brains.)

Engineering Focus

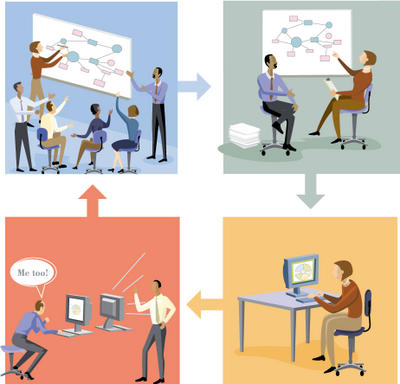

Doug is an engineer. An engineer is a person who maintains or controls an engine or machine. The engineer's job is to design or build machines, engines or electrical equipment, or things such as roads, railways or bridges, using scientific principles. Engineers are notorious for underestimating the impact of the human element. You'd no more rely on an engineering perspective to address deep organizational issues than you'd go to the surgeon for a headache. The logical approach of engineering is the opposite of the chaos of evolution. Engineers plan; evolution just happens. Engineering works top down to meet objectives; evolution happens bottom up and only the fit survive. Here's how an engineer might represent the process of augmenting intelligence or double-loop learning:

This is mechanical; it is not how nature works. And therein lies the problem.

Not an engineering problem

Doug and others had addressed process improvement as an engineering problem, when in fact it was a nature problem. Looking at a single, logical case (as implied by the diagram) is folly, for we're talking about human nature here, and that is anything but logical. At Accelerating Change 2005, Steve Jurvenson described a similar situation in science. (His blog has a rich description of this.)

Over dinner at O Chame

Last night it was my pleasure to have dinner with Dr. Herwig Rollett, the Head of Research Cooperation at the Know Center in Graz, Austria. He told me he'd been thinking about this area, which he calls collaborative cognition. It's described by its output rather than its process. DNA computing works this way.

Another design model

I had drawn a design model of a bucket into which several streams were pouring, and Herwig said that fit his understanding of DNA computing. You throw a lot of single DNA strands into the bucket, mix it up, and strain out those that have found a pair. This pairing up, sort of a mating ritual, is equivalent to massive parallel computing, and you don't find out what has been created until the end of the process.

Diversity required

As the business saying goes, "If two people in business always agree with one another, only one of them is necessary." When working with people instead of DNA, it's important for them to bring different mental models, whose combination may create something new and better.

to be continued

September 21

This evening I went to a presentation by Brian Behlendorf on Apache on the UC campus, after which he and I retired to a local cafe to talk about informal learning. He had brought up DNA computing so I asked him for links. He told me to check Andrew Hessel at University of Toronto, Drew endy @ MIT, and to search for Synthetic Biology.

The Apache Story

In 1995, Brian and seven others took advantage of NCSA's open license of its server software and began reworking it. Brian named the effort Apache because it was one of the last tribes to go and it's also a play on "patches," the medium by which the software is maintained. The Apache email list grew to 100 participants. (Every email from day one is still on line.) Three years later, Apache was running 60% of the servers on the internet. There was no company, just the name. They're weren't and still aren't any full time employees. It's a 100% volunteer effort. They became a non-profit foundation to limit their personal liability.

Apache's primary means of communication with its developer community is via its mail list, and with CVS ("the Volkswagen of version control tools") and its modern replacement Subversion. Bugzilla tracks bugs, and a Wiki coordinates discussion. Apache runs on concensus; the Linux project is a more directive air traffic control model.

Three rules for running an open source development effort:

1. Be humble. The Java community of Apache became toxic; it was disbanded.

2. Be transparent. Make decisions in the group. Keep the decision-making process open to all.

3. Think of the user community. Set up self-correcting mechanisms to address any potential Tragedy of the Commons situations. (Spam has ruined email. IM and VoIP are next in line.)

Look for passionate people. Fred Brooks says a top programmer outperforms a mediocre one by two orders of magnitude.

Communications skills are vital. These should be taught in school.

Everyone on the Apache team was self-taught. They read the online documentation (the "MAN" pages.) They explored. Linguistics majors were natural programmers. People learn Apache through observation and osmosis. They lurk. They watch how others respond to challenges. They incorporate other people's ideas in their work with grace.

Notes:

From Doug Engelbart's Bootstrap Institute

Among the Institute's missions:

- Enable a whole new way of thinking about the way we work, learn, and live together.

- Promote development of a collective IQ among, within, and by networked improvement communities.

- Share the A-B-C's of bootstrapping* and support co-evolution of human organizations and their tools.

Augmenting Human Intelligence

Friday, September 16, 2005

Gone Searchin'

Thursday, September 15, 2005

design thoughts

The future of education is outside of education. It is in the everyday life. In business, in the world. In life long learning. But the principles can be applied inside of formal education as well. They require a change in thinking, to move toward problem-centered, meaningful activities in the classroom. To exploit people's interests and subvert them to lead to natural, inspired learning activities. To exploit group interactions and social themes. To change teachers into guides and mentors. And to recognize that education should take place over a lifetime, not just in the formal classrooms of the first few decades of life.

You already know all that, right? That's exactly what you have just been taught. The hard part is making it happen, and that's where you will need all the skills you have learned: social change, social policy, human psychology, and human development. It is not going to be easy.

Speed (time)

Web: from communication to network

Static to dynamic content

Really just speeding the movie up

Like Disney Living Desert or cars racing

Flows

Inevitable.

Mobility

Ubiquity

Velocity

Sinking in:

Emergence

Uncertainty, surprise

Loose coupling

Barriers falling/openness

User content

Rated content

Humanity, not machines

Triple bottom line:

- Sustainable Earth

- Valuable Organization:

- Happy, productive people: connections & directions

levels of knowing & networking

COO SNA: who you think they know

KNETS: what you think they know

WHAT we know you... ad infinitum

Visibility drives down transaction costs

Reputation based on connections. Establishing ID a problem now.

NETS

for transactions

for trust

for communication

for power

Problems if these are not in sync

Traction: Groups with goals

CRM = customer exploitation management

circadian

People reach their peak of alertness between 6pm and 7pm according to

Circadian Technologies. From an evolutionary perspective, this time of

day, early evening, was most likely spent securing the hearth for a

safe night's sleep. Human alertness also rises at dawn or early

morning. While a CMO magazine piece warns employers that trying to mess

with this natural cycle won't get them very far, emerging

neurotechnologies from companies like Cortex Pharmaceuticals are making

are making headway on improving alertness and attention.

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

50000 year cycle

James Burke and the KnowledgeWeb

“Unfortunately, so much specialization falsely creates the illusion that knowledge and discovery exist in a vacuum, in context only with their own disciplines, when in reality they are born from interdisciplinary connections. Without an ability to see these connections, history and science won't be learnable in a truly meaningful way and innovation will be stifled.”

Humanity’s Evolutionary Journey by Duane Elgin

Our thinking is so locked into the framework of hunter-gatherer gives way to agriculture that gives way to the industrial age that ends with the information age that we are blind to a longer, more important cycle: the hero’s journey of humanity.

Elgin describes a 50,000 year cycle in which homo sapiens goes from being one with nature to developing a strong sense of self and thinking ourselves independent of nature. The uneasiness of our age results reconnecting with nature, this time with strong identities of our own.

It has taken roughly 50,000 years for us to pull ourselves free from absorption in nature and stand apart in our uniqueness. Now our hard-won separation threatens our survival. This is a pivotal time in our evolution: we have to choose whether to make a momentous turn to reconnect with the natural world and heal the separations that divide us-without losing the scientific understanding and technical sophistication we have gained. This may be the most important evolutionary turn that humanity will ever have to make.

Joe Jaworsky:

"Our mental model of the way the world works must shift from images of a clockwork, machinelike universe that is fixed and determined, to the model of a universe that is open, dynamic, interconnected, and full of living qualities."

Joseph Jaworski, Synchronicity: The Inner Path of Leadership, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1996.

Tachi Kiuchi, past chairman and CEO of Mitsubishi Electric America, has explored the workings of rainforests for insights on how to run a successful business. Writing in The Futurist, he states "If we ran our companies like the rain forest, imagine how creative, how productive, how ecologically benign we could be. We can begin by operating less like a machine and more like a living system."

There is substantial reason to believe that humanity can make this evolutionary leap forward. In addition to our enormous material and technical powers, we have four intangible powers that are even more transformative:

- the power of perspective -- to see the universe as alive and to consciously bring a soulful dimension into the human journey,

- the power of communication -- to engage in a new level of dialogue as a human family about our common future,

- the power of choice -- to voluntarily choose a sustainable and meaningful way of life, and

- the power of love -- to bring reconciliation and transformation into relationships of all kinds.

Thoughts: It’s Time to Grow Up

“We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

This goes back to Adam & Eve, to the dawn of consciousness. Our species has been growing up. Homo sapiens have been reading What Color is Your Parachute: Eternal Edition, and doing their information interviews for the last 50,000 years. Now it’s time for humanity to take the next step on the path, commit to a direction for the future, and start to work.

Letter:

I am in the midst of writing a book on Informal Learning that's taking me on a trip through humanistic psychology, network effects, culture shocks, complexity theory, and a bunch of other whistle-stops on the pathways through our deeply interconnected world. Sometimes I go into a state close to automatic-writing mode and learn from what pours out. A few minutes ago, pondering humanity's journey along the path of evolutionary consciousness, my fingers tapped out:"This goes back to Adam & Eve, to the dawn of consciousness. Since our species appeared as babes on the savannah, we have been growing up, ever so slowly. Homo sapiens have been reading What Color is Your Parachute: Eternal Edition, and doing their information interviews for the last 50,000 years. Now it’s time for humanity to take the next step on the path, commit to a direction for the future, and start to work."

Sunday, September 11, 2005

Herman Miller

What do executives want?

What’s important: today or tomorrow? Short-term results or longevity? As Peter Drucker once remarked, the successful business executive must have “his nose to the grindstone and his eyes to the hills.” Decisions are invariably a tradeoff of now vs. later. These translate into operational excellence (doing what we do now better) vs. transformation (seizing opportunity by doing something new).

Given a choice of today or tomorrow, senior managers want both. Indeed, the art of management is finding the right balance between the two. The IBM Global CEO Study 2004 summarized the views of 456 CEOs from around the world. Top execs are consistently looking for:

Primarily Operational Goals

Revenue growth from:

New products and services

New markets

Customer intimacy

New channels

Cost containment through:

Operational improvement

Infrastructure costs

Efficient customer service

Primarily Transformational Goals

Responsiveness to changing market conditions and risks, agility, to deal with:

Increased competition

Changing market dynamics

Marketplace behavior

Competition from new sources

New Distribution channels

Increasing customer power

Transformation

…but less than ten percent rate their record of change management in the past as successful

Both Operational and Transformational

A “customer responsive” organization, which takes:

Reduced cycle time, rapid response

Information for swift decisions

Continuous reinvention, adaptable processes for real-time response

Customer intimacy, hearing the voice of the customer

Source: Your Turn, The Global CEO Study 2004, IBM

Permissions Dr Abigail Tierney, EMEA Marketing Manager, IBM Business Consulting Services Abigail.tierney@uk.ibm.com

Informal learning is the path to transformation, for it involves exploring new territory that won’t be found in any formal curriculum. It also requires faith that the rewards of venturing outside one’s comfort zone outweigh the risks of stalking new ground.

Hearts & minds

Creating Passionate Users

Saturday, September 10, 2005

57 Optical Illusions & Visual Phenomena

Translate, translate, translate the summary

Remélangez.

This morning was I blog

from good reading blackbird,

which looks for an evaluation of

a special report APP concatenation,

if an article on highjacked

the concatenation 2.0 my attention.

The strength PC Web 2.0 of nets is the age,

where the people are enus

ven to be conscious that it is not the software,

which permits the concatenation of this of the topics

so much as services,

which are supplied over the concatenation.

Concatenation 1.0 was one age,

where the people could think

that Netscape (a software company) was,

the candidate for the crown

of the computer industry;

Concatenation 2.0 is one age,

where the people identify that the line

in the computer industry traditional

software companies changed over

to a new kind of the society of InterNet services.

At the place of the obvious conception,

which is the interface,

to satisfy the concatenation services

have the interfaces become

at this same contents after programs.

Jerry Michalski wrote recently that

Bill Gates and Arbeiten von Steve

created the independent systems,

while Doug considered angel beard,

to connect itself with others.

Microsoft struck the large time

with an operating system at plates

for the PC of the standard defacto from IBM.

But the documents of Microsoft are

too large for co-operation, and

its formats of commercial property

do not permit the concatenation

and remélange necessary for creativity.

Microsoft wants everyone

has a rich office experience,

Google wants that everyone

has a rich InterNet experience.

We are now used at this paradigm,

and an optimist can hope

that concatenation contents

will become only better with time:

metadata ajouté will be,

from the descriptions one keeps

more deeply clearer materials

and more complete references.

Remix

What a concept: the Web as Platform. Is that what Web 2.0 is? It depends on who you ask:

- Jon Udell (as quoted in a classic essay by Tim O'Reilly): "Don't think of the Web as a client-server system that simply delivers web pages to web servers. Think of it as a distributed services architecture, with the URL as a first generation "API" for calling those services."

- Deep Green Crystals: "The next generation of web applications will leverage the shared infrastructure of the web 1.0 companies like EBay, Paypal, Google, Amazon, and Yahoo, not just the "bare bones transit" infrastructure that was there when we started..."

- Jeff Bezos: "web 2.0...is about making the Internet useful for computers."

- computeruser.com: "Yesterday’s challenge of producing elegant and database-driven Web sites is being replaced by the need to create Web 2.0 'points of presence'"

- Mitch Kapor: "The web browser and the infrastructure of the World Wide Web is on the cusp of bettering its aging cousin, the desktop-based graphical user interface for common PC applications."

Evolution of Web 2.0

In the late 90s and especially the first few years of the 21st century, the advent of XML technologies and Web services began to change how sites were designed. XML technologies enabled content to be shareable and transformable between different systems, and Web services provided hooks into the innards of sites.

Enter Web 2.0, a vision of the Web in which information is broken up into “microcontent” units that can be distributed over dozens of domains. The Web of documents has morphed into a Web of data. We are no longer just looking to the same old sources for information. Now we’re looking to a new set of tools to aggregate and remix microcontent in new and useful ways.

(This makes me wonder if the all the fuss about learning objects is barking up the wrong tree. Why invent a new way to replicate what the mainstream web is going to do anyway? Clay Shirky: "The mass amateurization of publishing means the mass amateurization of cataloging is a forced move.")

Networks trump PCs

Instead of visual design being the interface to content, Web services have become programmatic interfaces to that same content. This is truly powerful. Anyone can build an interface to content on any domain if the developers there provide a Web services API.

Jerry Michalski recently wrote that both Bill Gates and Steve Jobs created stand-alone systems while Doug Engelbart envisioned connecting with others. Microsoft hit the big time with a disk operating system for IBM's defacto standard PC.

- I bought one of the early IBM PCs. Connecting to the outside world involved buying a Hayes modem and some shareware software (I used Andrew Fluegelman's PC-Talk). This enabled me to participate in bulletin boards at a blazing 300 baud.

- Jobs then took the highly networked visions created at Xerox PARC and somehow turned out a brilliant, but completely isolated little anthropomorphic machine. For some time, he didn't want it to have a hard drive, a network or a larger/color monitor. Sheesh.

Other people? Other places? They're over there, on the H: drive or in the "collaboration" application.

Why have these magical platforms neglected our social nature for so long? Why are these features still being glued on as afterthoughts, like antlers on a jackalope? Can't we loosen up, move things around a bit so that collaboration, annotation, search and linking are always at hand, for every object, as native functions of every window?

Web 2.0 is going to change all that. The future resides in connections.

Whither Microsoft?

Microsoft's ... focusing on yesterday's market. Microsoft's dominance of the desktop is as relevant to the future of computing as Union Pacific's dominance of the railroads was to the future of transportation in the twentieth century. Here's a sampling of reasons why Microsoft is history:

- Microsoft wants everyone to have a rich desktop experience, Google wants everyone to have a rich Internet experience.

- Microsoft's business model depends on everyone upgrading their computing environment every two to three years. Google's depends on everyone exploring what's new in their computing environment every day.

- Microsoft looks at the world from a perspective of desktop+Internet. Google looks at the world from a perspective of Internet+any device.

- Microsoft wants computers to help individuals do more unaided. Google wants computers to help individuals do more in collaboration. In the Internet age, who wants to work alone any more, when all the unexplored opportunity is in collaborative endeavor?

Communities Building Social Information

Let’s say, for example, that we tag a bookmark “Web2.0” in Del.icio.us. We can then access del.icio.us/tag/Web2.0 to see what items others have tagged similarly, and discover valuable content that we may not have known existed. A search engine searches metadata applied by designers, but Del.icio.us leverages metadata applied by folks who don’t necessarily fit that mold.

Check what you get by going to http://del.icio.us/tag/web2.0 Of course, you're seeing a page generated especially for you. It's probably quite different from the page I looked at.

Now software and systems are embracing flexibility and bottom-up change. Users can give as well as take. Intelligent networks are becoming much more important than any of their nodes. Computing is adapting to us. We're headed in the direction Jerry called for when he asked for us to loosen up, move things around a bit so that collaboration, annotation, search and linking are always at hand, for every object, as native functions of every window. Connections count!

Let's go up on the balcony and take a look at the patterns of this loosely-defined Web 2.0. From here, many aspects of Web 2.0 are parallel to what I envision coming in corporate learning. Bottom-up, read/write, addressable chunks, application independence, mash-up and remix, and integration with real life.

Let's go up on the balcony and take a look at the patterns of this loosely-defined Web 2.0. From here, many aspects of Web 2.0 are parallel to what I envision coming in corporate learning. Bottom-up, read/write, addressable chunks, application independence, mash-up and remix, and integration with real life.So, is there a future in text-remix? Should Jay become a TJ (text jockey)?

I pointed Copernic Summarizer at the text then on this page and requested a 250-word summary.

Remix.

This morning I was reading Robin Good's blog, looking for an assessment of a particular web conferencing app, when an article on Web 2.0 highjacked my attention.

Networks trump PCs. Web 2.0 is the era when people have come to realize that it's not the software that enables the web that matters so much as the services that are delivered over the web.

Web 1.0 was an era when people could think that Netscape (a software company) was the contender for the computer industry crown; Web 2.0 is an era when people are recognizing that leadership in the computer industry has passed from traditional software companies to a new kind of internet service company. Instead of visual design being the interface to content, Web services have become programmatic interfaces to that same content.

Jerry Michalski recently wrote that both Bill Gates and Steve Jobs created stand-alone systems while Doug Engelbart envisioned connecting with others. Microsoft hit the big time with a disk operating system for IBM's defacto standard PC. But Microsoft documents are too large for collaboration, and their proprietary formats don't allow the linking and remixing needed for creativity.

Microsoft wants everyone to have a rich desktop experience, Google wants everyone to have a rich Internet experience.

We are used to this paradigm now, and an optimist can hope that Web content will only get better with time: metadata will be added, descriptions will get deeper, topics more clear, and references more comprehensive.

Wednesday, September 07, 2005

fast company on mihaly

The Art of Work

These words, written by American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Mee-high CHICK-sent-me-high-ee), describe the state of "flow." It's a condition of heightened focus, productivity, and happiness that we all intuitively understand and hunger for.

Csikszentmihalyi's groundbreaking book on the subject, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (Harper & Row Publishers Inc., 1990), has been lauded by such heavyweights as Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and Jimmy Johnson, who credited it with helping him coach the Dallas Cowboys to a Super Bowl win in 1993. Yet although the quest for flow immediately resonated with the sporting and leisure worlds, the concept never got much traction in business, possibly because ecstasy and the workplace go together about as well as tomatoes and chocolate.

In the past few years, however, many major companies, including Microsoft, Ericsson, Patagonia, and Toyota have realized that being able to control and harness this feeling is the holy grail for any manager -- or even any individual -- seeking a more productive and satisfying work experience.

These companies are now using Csikszentmihalyi's ideas to learn how they can get the best out of their workers or create more compelling connections with their customers. Without flow, there's no creativity, says Csikszentmihalyi, and in today's innovation-centric world, creativity is a requirement, not a frill. "To stay competitive, we have to lead the world in per-person creativity," says Jim Clifton, CEO of the Gallup Organization, which provides management consulting for 300-odd companies. "People with high flow never miss a day. They never get sick. They never wreck their cars. Their lives just work better." Clifton says flow is one ideal outcome of Gallup's consulting work.

No one is more surprised about the corporate world's increasing interest in his research than Csikszentmihalyi, 71, the former head of the psychology department at the University of Chicago. Now director of the Quality of Life Research Center at the Drucker School of Management in Claremont, California, he has been studying flow for more than four decades. Csikszentmihalyi was born in Italy; his father, the Hungarian consul there, was sentenced to death in absentia for not returning to Hungary after the Soviet takeover in 1948. In 1956, at the age of 22, Csikszentmihalyi came to the United States with $1.25 in his pocket.

An avid rock climber, Csikszentmihalyi took note of the special feeling he got while inching his way up a challenging rock face, and began thinking about it in terms of his psychology studies. Why, he wondered, was the entire field of psychology focused exclusively on the study of human pathology and dysfunction? What about the positive states, the moments when human beings are at their absolute best?

Csikszentmihalyi spent hours interviewing and observing exceptionally creative people, including leading chess players, rock climbers, composers, and writers, and normal folks as well, as they did their work. He also developed a unique research tool called Experience Sampling Method, in which his study subjects carried pagers for a week at a time. Beeped randomly eight times throughout the day, they wrote down what they were doing and feeling right at that moment.

Csikszentmihalyi, who with his white hair and beard resembles a tall and reticent Santa Claus, discovered that the times when people were most happy and often most productive were not necessarily when they expected they would be. Passive leisure activities such as TV-watching consistently ranked low on participants' scales of satisfaction -- even though they often sought out these experiences. Instead, people reported the greatest sense of well-being while pursuing challenging activities, sometimes even at work, and often while immersed in a hobby.

In the flow state, Csikszentmihalyi found, people engage so completely in what they are doing that they lose track of time. Hours pass in minutes. All sense of self recedes. At the same time, they are pushing beyond their limits and developing new abilities. Indeed, the best moments usually occur when a person's body or mind is stretched to capacity. People emerge from each flow experience more complex, Csikszentmihalyi found. They become more self-confident, capable, and sensitive. The experience becomes "autotelic," meaning that the activity actually becomes its own reward. "To improve life, one must improve the quality of experience," he says. One of the chief advantages of flow is that it enables people to escape the state of "psychic entropy," the distraction, depression, and dispiritedness that constantly threaten them.

Csikszentmihalyi, a classic academic, has resisted many overt attempts to commercialize flow, particularly in the business world. "I'm not claiming that flow is like a magic pill," he says. "I'm always a little worried that if you ramp it up to a large company without knowing the culture and the context, it might not work." Don't bother looking for "7 Habits of Flow at Work" here: Csikszentmihalyi is the anti-Stephen Covey.

Yet plenty of others see the flow of dollar signs, either in their own company's performance or in bringing the concept to the corporate masses. Back in 2002, Stefan Falk, then the vice president of strategic business innovation at Ericsson, was given the task of integrating the merger of two huge business units worth $16 billion. Layoffs were coming, and Ericsson hoped Falk could find a way to make the remaining workers more productive. A former McKinsey & Co. consultant, Falk and a colleague had stumbled across Flow and another Csikszentmihalyi book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (HarperCollins, 1996), while conducting a multiyear study at McKinsey on human development and motivation. "I was mesmerized when I read it," Falk says. "I had a vital piece of the puzzle. I said to my friend, 'I think we should contact this guy whose name I cannot pronounce.' "

So he did (like many others, Falk calls Csikszentmihalyi "Mike" for the sake of simplicity). The two discussed Mike's belief that flow has several necessary preconditions. These include having clear goals and a reasonable expectation of completing the task at hand. People must also have the ability to concentrate, receive regular feedback on their progress, and actually possess the skills needed for that type of work.

Falk concluded that the best way to get to flow was to have Ericsson managers spend a nearly unheard-of amount of quality time with each one of their employees. Managers were asked to work with employees to draw up separate "performance contracts" that included an assessment of each worker's strengths and weaknesses and set out a very specific action plan to help improve their skills. It all sounds pretty standard, but there was a kicker: To monitor progress, managers would meet with each employee six times a year for intensive one-on-one sessions lasting as long as an hour and a half each.

At first, the managers groused at the extra work. Falk's response: "What are you managing? The only thing you really manage here is your employees. End of story." This fall, Ericsson will export the new management system to all of its offices around the world.

Falk moved on to Green Cargo, one of Scandinavia's largest transport and logistics companies, in mid-2003, and instituted an even more comprehensive flow-based management overhaul. Every single month, he required meetings between employees and managers, 150 of whom were sent Flow to read as part of a six-day training process. Performance-review contracts were drawn up to cover three-month periods, and then renegotiated. Before each meeting, workers were asked to spend at least an hour reflecting on what had transpired since the previous one and determining the content of the upcoming one.

It seems most ironic that more meetings would lead to better flow, but these aren't your normal stultifying interdepartmental snorefests. Instead, they are one-on-one intensives akin to an executive coaching session. So far so good: Last year, government-owned Green Cargo turned a profit for the first time in its 120-year history, and Falk's work gets much of the credit, says Johan Saarm, Green Cargo's deputy CEO.

In a world teeming with authors lusting for the speaking circuit, Csikszentmihalyi is a refreshing oddity. Although business is clamoring for more and more of him, his relationship with the private sector remains ambivalent; he even recently organized a conference called "Alternatives to Materialism." Csikszentmihalyi says he never really thought about business until five years ago, when he was offered the post at Drucker. He accepted it in part because he liked his potential colleagues, and also because it was a quiet place with good weather for his wife's tortured sinuses. "I lived my life in an ivory tower, and business was to be held at an arm's length," he says, Birkenstocks poking out below his slacks and blazer. That may be because none of his research has established any link between happiness and the possession of lucre.

It may also be because there is a dark side to flow, says Csikszentmihalyi. It can come while pursuing destructive activities, such as addictions or crimes. He offers the contrasting examples of Mother Teresa and Napoleon Bonaparte to show how differently the flow state can affect the world. The same is true of business; it's easy to imagine Enron's Andrew Fastow in a rapturous flow state as he plotted his next scheme.

Yet if Csikszentmihalyi feels he can make a difference, he will speak to companies, and currently takes about 10 corporate speaking engagements a year. A few years ago, he gave a talk at Microsoft, which is studying how to use flow to give Windows users a more engaging experience. If the notoriously buggy and user-unfriendly operating system suddenly becomes a pleasure to use, Csikszentmihalyi deserves some thanks. Elsewhere at Microsoft, a researcher is studying how flow might improve the lives and productivity of software engineers.

At Patagonia, CEO Michael Crooke seized upon the ideas in Flow earlier than most. He read the book 10 years ago and credits it with explaining to him exactly why he thrived as a Navy Seal. "When you get a high-powered team together and you really get into a zone, you'll synchronize," he says. Crooke sought Csikszentmihalyi out, and has been meeting with him weekly for the past four years while working toward a PhD in management. Much of his dissertation focuses on creating a workplace environment conducive to flow.

Crooke's research laboratory is his own company. He believes the flow experience can extend from the Patagonia worker to the customer if they both feel good about what the company stands for. Flow, he says, "is at the center of everything I'm doing." In April, Crooke sent out the first iteration of an annual survey intended to gauge how much meaning and job satisfaction employees find in their work. It is chock-full of probing questions like how free employees feel to use their own judgment, whether they feel management is fully open about financial matters, whether Patagonia adequately reports environmental damage it causes, and whether its corporate values and its workers' personal values are aligned.

Crooke is also examining to what extent Patagonia's famed goal of protecting the environment affects his workers' experiences there. This is because Csikszentmihalyi believes that flow is most powerful when achieved in service of a goal that will better society. After learning how much pesticide was required to make a single cotton shirt, Patagonia began using only organic cotton in its clothes. In a few years, Crooke says, Patagonia will make biodegradable clothing that people can compost in the backyard along with their banana peels.

Some people dispute a direct linkage between earth-friendly underwear and an inspirational workplace, but Crooke isn't one of them. "[Flow] manifests itself in focused, on-time, on-spec products," he says, "that win in the marketplace because they were developed in a system in which the customers and the internal people all know what they want and need." In a world of depressed Dilberts, it's certainly worth a try.

Out of the zone

Renewable energy systems will be a major focus at the university alongThat's how to learn: getting out of one's comfort zone.

with a heavy emphasis on interdisciplinary research. As a graduate of

UCLA who developed my own interdisciplinary education across three

schools (evolutionary biology, environmental science and then a

graduate degree in economic geography), I hope that UC Merced will

continue to devote resources to help students cross traditional

boundaries.

It looks like they are starting out with a good foundation. As Jessica

Green, assistant professor in the UC Merced School of Natural Sciences

put it,"...it's cool, I sit next to a philosophy professor, a Chinese

historian, a mathematician, a physicist and a poet." If that's not

interdisciplinary, then I don't know what is.

Come to think of it, interaction with people who are not like us take us into their comfort zones and out of ours. We learn where we don't overlap.

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Amy Jo Kim

Nine Timeless Design Strategies

The book is organized around nine timeless design strategies that characterize successful, sustainable communities. Taken together, these strategies summarize an architectural, systems-oriented approach to community building that I call "Social Scaffolding:"

Define and articulate your PURPOSE

Communities come to life when they fulfill an ongoing need in people's lives. To create a successful community, you'll need to first understand why you're building it and who you're building it for - and then express your vision in the design, navigation, technology and policies of your community.![]()

Build flexible, extensible gathering PLACES

Wherever people gather together for a shared purpose, and start talking amongst themselves, a community can begin take root. Once you've defined your purpose, you'll want to build a flexible, small-scale infrastructure of gathering places, which you'll co-evolve along with your members.![]()

Create meaningful and evolving member PROFILES

You can get to know your members - and help them get to know each other - by developing robust, evolving and up-to-date member profiles. If handled with integrity, these profiles can help you build trust, foster relationships, and deliver personalized services - while infusing your community with a sense of history and context.![]()

Design for a range of ROLES

Addressing the needs of newcomers without alienating the regulars is an ongoing balancing act. As your community grows, it will become increasingly important to provide guidance to newcomers – while offering leadership, ownership and commerce opportunities to more experienced members.![]()

Develop a strong LEADERSHIP program

Community leaders are the fuel in your engine: they greet visitors, encourage newbies, teach classes, answer questions, and deal with trouble-makers before they destroy the fun for everyone else. An effective leadership program requires careful planning and ongoing management, but the results can be well worth the investment.![]()

Encourage appropriate ETIQUETTE

Every community has it’s share of internal squabbling. If handled well, conflict can be invigorating - but disagreements often spin out of control, and tear a community apart. To avoid this, it’s crucial to develop some groundrules for participation, and set up systems that allow you to enforce and evolve your community standards.![]()

Promote cyclic EVENTS

Communities come together around regular events: sitting down to dinner, going to church on Sunday, attending a monthly meeting or a yearly offsite. To develop a loyal following, and foster deeper relationships among your members, you'll want to establish regular online events, and help your members develop and run their own events.![]()

Integrate the RITUALS of community life

All communities use rituals to acknowledge their members, and celebrate important social transitions. By celebrating holiday marking seasonal changes, and integrating personal transitions and rites of passage, you’ll be laying the foundation for a true online culture.![]()

Facilitate member-run SUBGROUPS

If your goal is to grow a large-scale community, you'll want to provide enabling technologies to help your members create and run subgroups. It's a substantial undertaking -- but this powerful feature can drive lasting member loyalty, and help to distinguish you community from it's competition

Support Economy Principles

The Support Economy Principles

-

All value resides in individuals: Individuals are recognized as the source of all value and all cash flow. Distributed capitalism thus entails a shift in commercial logic from consumer to individual as momentous as the 18th-century shift in political logic from subject to citizen.

-

Distributed value necessitates distributed structures among all aspects of the enterprise: As value moves to the individual via the federations and advocates, production, ownership and control also become distributed, devolving power.

-

Relationship economics is the framework for wealth creation: Enterprises and federations invest in commitment and trust to maximize realized relationship value. Wealth is created in the realization of relationship value and depends on the quality of 'deep support' (see principle #5).

-

Markets are self-authoring: Markets for 'deep support' are formed as individuals opt into fluid constituencies that hold the possibility of community.

-

Deep support is the new meta-product: Relationship value is realized as the enterprise assumes total accountability and responsibility for every aspect of the consumption experience.

-

Federated support networks are the new competitors: They achieve economies and differentiation through their configuration, quality and deep support, providing unique aggregations of products and services.

-

All commercial practices are aligned with the individual: No cash is released into the federation (and the underlying enterprises) until the individual pays. Cash flow is thus the essential measurement of value realization.

-

Infrastructure convergence redefines costs and frees resources: By eliminating the replication of administrative activities that exist in today's organizations, convergence dramatically lowers operating costs and working capital, putting 'deep support' within the reach of individuals at all income levels.

-

Federations are infinitely configurable: Each individual or constituency determines the right configuration for 'deep support' he needs, and each configuration is an endlessly renewable resource for competitive advantage.

-

New valuation methods reflect the primacy of the individual: Competitiveness depends on ability to nurture and leverage new intellectual, emotional, behavioural and digital assets defined by individual needs.

-

New consumption means new employment: A new employment relationship including new career rights, and a managerial canon of collaborative coordination are necessary consequences of relationship economics.

Monday, September 05, 2005

CLO Articles

- The Learner Lifecycle

- Useful Things

- Extreme Learning: Decision Games

- Meta-Lessons From the Net

- The Business Singularity

- Improv Education

The first wave of e-learning brochures invariably touted the benefits of focusing on the learner. Schools and classes had always been organized for the convenience of the faculty—one size fits all. In the e-era, learners received personalized instruction—just what they needed, just when they needed it. It was “learner-centric.”

- What Counts?

Businesses exist to create value, and the source of value resides outside the learning function. As Peter Drucker has pointed out, “Neither results nor resources exist inside the business. Both exist outside. The customer is the business.”

- Who Knows?

What would you think of an assembly line where workers didn’t know where to find the parts they were supposed to attach? Absurd, you say. Heads would roll. Yet for knowledge workers, this is routine.

- Emergent Learning

Not so long ago, e-learning was a utopian dream. Networked learning would educate the world. E-learning promoters saw themselves as innovators writing corporate history. Excitement filled the air.That future has arrived. Today a healthy percentage of learning in corporations is technology-assisted. At first we thought it was all about content, but context-free courseware failed for lack of human support. Pioneering online communities turned into ghost towns.

- Personal Intellectual Capital Management

Ultimately, you’re responsible for the life you lead. It’s up to you to learn what you need to succeed. That makes you responsible for your own knowledge management, learning architecture, instructional design and evaluation.

- Connections: The Impact of Schooling

Your 16-year-old daughter says she’s going to take sex education at school and you’re relieved, but she tells you she plans to participate in sex training and you’re unnerved. Why? Because outside of education, you learn by doing things.Small wonder that executives hear the word “learning,” think “schooling” and conclude “not enough payback.” Executives respond better to “execution.”

- Informal Learning: A Sound Investment

Workers who know more get more accomplished. People who are well connected make greater contributions. The workers who create the most value are those who know the right people, the right stuff and the right things to do.It’s all a matter of learning, but it’s not the sort of learning that is the province of training departments, workshops and classrooms. At work we learn more in the break room than in the classroom. We discover how to do our jobs through informal learning—observing others, asking the person in the next cubicle, calling the help desk, trial and error and simply working with people in the know. Formal learning—classes and workshops and online events—is the source of only 10 percent to 20 percent of what we learn at work.

Saturday, September 03, 2005

Let's be human

Articles on Meg’s Website:It's An Interconnected WorldShambhala Sun, April 2002

Can We Reclaim Time to Think?Shambhala Sun September 2001

Goodbye, Command and ControlLeader to Leader, July 1997 Margaret Wheatley©

The Irresistible Future of OrganizingJuly/August 1996Margaret J. Wheatley and Myron Kellner-Rogers

A number of years ago, having failed to conform to my employer’s standards of behavior, I attended the Center for Creative Leadership to be re-programmed. Toward the conclusion of the workshop, our instructor put some rocks on the floor and began to jabber about relativity, aura, vibrations, and other magic, attributing it to recent findings in physics. I interrupted, earning the enmity of half my peers when I said, “That is the biggest heap of bullshit I have heard in years.”

“No,” he said. “Margaret Wheatley said this. It’s true.” Not knowing who Margaret Wheatley was at the time, I said I didn’t care. It seemed like bad science to me. The instructor stood by his guns. And then came one of life’s marvelous moments. A fellow two seats to my right said, “I have a doctorate in theoretical physics, and Jay is absolutely right. What you’re telling us is nonsense.” Hoo-hah! It was like Woody Allen pulling Marshal McLuhan from out of nowhere to put down a pompous Columbia instructor standing in line for the movies. Take THAT!

Irony of ironies, I just finished reading Meg Wheatley’s Finding Our Way and am enthralled. There’s no mention of making incantations over pebbles. Rather, she points out where Western culture went off the rails by mistaking men for machines and picking up on other industrial-age chimera.

When the forms of an old culture are dying, the new culture is created by a few people who are not afraid to be insecure. Rudolf Bahro

Our dilemma began three hundred years ago. We thought we’d figured out how the universe worked (like a giant clock) and we could bring it under our control. Better to look at the world through the lens of nature: it’s alive. Organizations as organisms.

Maturana and Varela tell us that only 20% of what we see of the world originates outside of ourselves. Most of what we visualize comes from us, not from what we’re looking at. They also write that you can never control a living system; the best you can do is to disturb it. Organizational smarts comes from people’s ability to enter a world in whose significance they share.

Life lives on the edge that separates stability from chaos. It needs enough stability to maintain its identity and meaning, balanced by enough chaos to let change get in.

The capacity for self-organization exists within organizations. Leaders must foster an environment to let it thrive. Such leaders start with intentions, not plans. “The road is your footsteps, nothing else,” wrote the South American poet Machados.

Decades of being bounced around by downsizing, re-engineering, picky rules, controlling bosses, and being put in boxes have made workers cynical and suspicious.

“Once we stop treating organizations and people as machines and more to the paradigm of living systems, organizational change is not a problem.”

“Western culture developed a strangely negative and unfamiliar view of humans as machines. This resulted in a collective view of us as passive, unemotional, fragmented, incapable of self-motivation, disinterested in meaningful questions or good work.”

“We’re under so much stress that all we do is look around the organization to find somebody we can shoot.” (And the executive quoted is a nun!)

People cannot help but be creatively involved in how their work is done. They only support what they create. Life insists on its freedom to participate. This reminds me of my old concept of giving a person freedom as long as they remain in the sandbox that is created for them.

We do not see reality. What you choose becomes your life.

More and better inner connections make for a healthier living system. Standards and measures are imposed on machines from outside. Organizations figure them out as they go along, as people deal with situations.

Good experimentation is a process. This is similar to my process view that nothing ever ends. Four questions lead to the 1-2-3 model….

- Who else needs to be here? (Relationships are considered)

- What just happened? (Learn from it, don’t blame)

- Can we talk? (Others have different perceptions)

- Who have we become? (Actions. We are what we do.)

Nothing living lives alone. Life always and only organizes as systems of interdependency.

On process: “It hasn’t been easy to give up the role of master creator and move into the dance of life. As our dance partner, life insists that we put ourselves in motion, that we learn to live with instability, chaos, change, and surprise.”

Like Meg, I recollect joining this dance. My systems mantras that everything’s connected, nothing ever ends, you can never do just one thing, life is unpredictable, logic is not king, everything flows. Uncertainty? Not a problem. It beats kidding yourself.

I’m looking over my own shoulder now, contemplating how I learn. This is important stuff in my study of informal learning, but as Meg says, I long to put my stamp on it, to claim it as mine. Part of this, I accomplish with selectivity. I claim a paragraph or two per chapter. They’re items I highlighted in neon yellow while reading. If an important passage doesn’t get highlighted, I’m probably going to forget it before I wake up tomorrow.

Meg has a wonderful list of obsolete, harmful beliefs.

- Organizations are machines (nothing new there)

- Only material things are real. (it’s amazing how many people think intangibles do not exist)

- Only numbers are real. (As if….)

- You can only manage what you can measure.

- Tech is always the best solution.

KM is “thing” thinking. Capture, inventory, etc.

In survey after survey, workers report that most of what they learn about their job, they learn from informal conversations.

F2F meetings are important for knowledge sharing.

Feedback is self-generated. An individual and a system notice whatever they determine is important for them. They ignore everything else.

There is no such thing as cause and effect.

When we listen with less judgment, we always develop better relationships with each other.

We create ourselves by what we choose to notice. Once this work of self-authorshiop has begun, we inhabit the world we’ve created. We self-seal.

thoughts on the book

from bob's work... i must help the reader by making the backbone of the book clear.

also, what does the reader want? access to what to do is part of it were i the reader, i'd want:

- immediately accessible subject matter

- ability to skim and get it

- logical flow or narrative i can plant in my head

- visual as well as written content

- learning model and model of ecosystem

- ecosystem=optimize this unit complexity

- garden=organization seasons, harmony

- tree=individuals lifecycle

borrow from nature...

small pieces loosely joined?

reflection: time for this and schmooze being eaten by blackberry. out of balance.

rely on people to do the right thing: village behavior takes a village

prototypicle chapter

- visual language & verbal topic

- story/case

- observations

- commentary from salons

- takeaway

- profile of exemplar

The Earth's biosphere is made up small interacting entities called ecosystems. In an ecosystem, populations of species group together into communities and interact with each other and the abiotic environment. The smallest lining entity in an ecosystem is a single organism. An organism is alive and functioning because it is a biological system. The elements of a biological system consist of cells and larger structures known as organs that work together to produce life. The functioning of cells in any biological system is dependent on numerous chemical reactions. Together these chemical reactions make up a chemical system. The types of chemical interactions found in chemical systems are dependent on the atomic structure of the reacting matter. The components of atomic structure can be described as an atomic system.

the food chain

Equilibrium

Equilibrium describes the average condition of a system, as measured through one of its elements or attributes, over a specific period of time. For the purposes of this online textbook, there are six types of equilibrium:

(1) Steady state equilibrium is an average condition of a system where the trajectory remains unchanged in time.

Feedbacks

In order for a system to maintain a steady state or average condition the system must possess the capacity for self-regulation. Self-regulation in many systems is controlled by negative feedback and positive feedback mechanisms. Negative-feedback mechanisms control the state of the system by dampening or reducing the size of the system's elements or attributes. Positive-feedback mechanisms feed or increase the size of one or more of the system's elements or attributes over time.

Interactions among living organisms, or between organisms and the abiotic environment typically involve both positive feedback and negative feedback responses. Feedback occurs when an organism's system state depends not only on some original stimulus but also on the results of its previous system state. Feedback can also involve the system state of non-living components in an ecosystem. A positive feedback causes a self-sustained change that increases the state of a system. Negative feedback causes the system to decease its state over time. The presence of both negative and positive feedback mechanisms in a system results in self-regulation.

Best sources for thinking like this are probably Out of Control, It's Alive, and Finding Our Way.

Maybe check out natural capitalism. Find an ecologist. Paul Hawken? Michael Rothschild? Stuart Brand?